Although I’ve been a

fan of Anne Thackeray Ritchie’s (1837-1919) work

for some time, I recently renewed this appreciation due to an unexpected

question. Matthew

Roy, a fellow George MacDonald fan, emailed me to ask if I knew of any

fairy tales which address experiences of pregnancy; as he commented, ‘There is an

infertility convention in a lot of fairy tales (‘Snow White’, ‘Thumbelina’, ‘Little

Tom Thumb’, ‘The Light Princess’, etc.), but the problem is usually overcome in

a matter of sentences, perhaps after having talked with some sort of magical

character (a frog, a witch). In the end the woman becomes pregnant, and then

"gives birth to a baby girl with hair as black as coal, skin as white as

snow..." But nothing about actually being pregnant or actually giving birth.’

This is unfortunately very often true, probably

because people who wrote and collected them were generally men, in times when

men didn't tend to engage as actively with pregnancy experiences as they do now.

However, the French

female fairy tale salon writers of the seventeenth-early eighteenth centuries

offer a slightly different perspective. One of the most famous of these

writers, Madame d'Aulnoy (1650-1705), herself had six children, and there is a

consciousness to be seen of the pregnancy and birth experience in some of her

tales (‘Princess Mayblossom’, ‘The Benevolent Frog’, and ‘The Good Little Mouse’ in particular),

which trace the pregnancy experience of various beleaguered queens over some

paragraphs as they flee danger and encounter helpful fairies, frogs and

more. In her book Pregnant

Fictions: Childbirth and the Fairy Tale in Early-modern France, Holly

Tucker argues that the often magical dangers that these women face dramatize

the more general concerns often felt by pregnant women -- particularly in times

when medical knowledge and assistance could be unpredictable, to say the least

– and that some of the fairies/magical creatures who help these queens

represent midwives. In this way (as well as in others, but that’s another day),

D’Aulnoy’s work evokes experiences of female community which transcend time and

genre.

Some of the work of Madame d’Aulnoy, unlike

others of her salon colleagues, can be found quite readily online; thanks to

the lovely people at SurLaLuneFairytales, but also to a

Victorian team of female translators and editors – one of which is Anne

Isabella Thackeray Ritchie (Miss Annie

Macdonell and Miss Lee were the translators). In addition to her prolific literary

output in a variety of disciplines, Thackeray Ritchie produced a) witty and

insightful fairy tale adaptations and b) a collection of Madame d’Aulnoy’s work,

(1892). In reading the introduction to this collection the other day, I was

struck by the trouble Thackeray Ritchie takes to explore d’Aulnoy’s female

community in personable detail.

She notes that d’Aulnoy’s

circle included Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, the author of ‘La Belle et la

Bête’ [‘Beauty and the Beast’], and that: ‘Any of us in the nineteenth century,

who have thrilled to the stirring and beautiful song of "Che Faro,"

as uttered by the sweet voice of Julia Ravogli in "Orfeo," have

witnessed a scene reproduced out of one of Madame d'Aulnoy's histories, in

which Love, crowned with roses, is sent to assist the wandering prince in his

search through Hades for her whom he adores.’

Through these references, she locates d’Aulnoy in a female artistic

context, both literary and musical, which is only enhanced by her statement

that ‘The prettiest of Madame d'Aulnoy's stories are also the best known, such

as L'oiseau Bleu, The White Cat, Le Prince Lutin, and a good many others. Le

Nain Jaune, Fortunéc, La Biche au Bois, are also very charmingly told’.

Moreover, Thackeray

Ritchie also celebrates d’Aulnoy and her female community in biographical detail.

She observes complexities around cultural perceptions of beauty, but emphasises

her intelligence:’ "She was always ready in

conversation," says one of her admirers. "No one knew better how to

introduce an anecdote, and her stories were the delight of all."’ Thackeray Ritchie observes d’Aulnoy’s

strained family life, both before (upon the birth of a younger brother, d’Aulnoy

was promptly dispatched to a nunnery, against her will, where she took refuge

in ‘read[ing] a great many novels about romantic heroes and "heroesses,"

as she is made to call them, and [trying] to pose as a heroess herself a great

deal more than the abbeys approved’) and after marriage (‘Madame d'Aulnoy

speaks with cordial dislike of her husband, with whom she seems to have lived

very unhappily from the first, and from whom, whenever anything went wrong, she

seems to have run away in disguise’). M. d’Aulnoy suffered imprisonment and near execution

due to false accusations of treason by a group of conspirators. Thackeray Ritchie describes, in detail, d’Aulnoy’s

personal connection to a friend, ‘"the famous and beautiful Madame

Angélique Tiquet "’. Having

suffered even more than d’Aulnoy from an unhappy and abusive marriage, Madame

Tiquet tried to kill her husband; for this she is tried and eventually

executed. D’Aulnoy, notes Thackeray

Ritchie, proved a loyal friend, trying to help Madame Tiquet escape and

speaking at her trial (which meant that d’Aulnoy was ‘somewhat compromised’).

Thackeray Ritchie goes on to explore d’Aulnoy’s

life and other works, including her creative approach to citations,

observations and referencing in her memoirs (‘Madame

d'Aulnoy, although she had excellent opportunities of observing facts, and was

in the main accurate, had the singular habit of transcribing entire paragraphs

out of the books of other people without any acknowledgment whatever, and also

of sometimes adding imaginary adventures when her own struck her as somewhat

dull’). I do not have the scope

to explore these here, but would encourage you to take a look.

But then, it’s not surprising that

Thackeray Ritchie should have been interested in d’Aulnoy’s female community.

She herself wrote two texts explicitly extolling female literary tradition: Book of Sibyls (1883)

and A Discourse on Modern

Sibyls

(1913), in which she explores a number of eighteenth – and nineteenth-century

female authors (Maria Edgeworth, Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, and George

Eliot form a few examples). Through these, Thackeray

Ritchie celebrates contemporary nineteenth-century female intelligence,

storytelling and wisdom with mythological connotations (the Sibyls were ancient

prophetesses and sources of wisdom -- not to mention plot foreshadowing

--- in classical mythology). Her version of Cinderella (in Five Old Friends and a Young Prince,

1868) paints ‘Ella Ashford’’s godmother as an eccentric, rich Victorian society

hostess, Lady Jane Peppercorne, who would fit quite nicely in a silver-fork

novel or in the memoirs of Lady Dorothy Nevill (gardener, noted

conversationalist, and society hostess). Ritchie’s use of female storytelling

(of whatever sort) traditions creates figures which transcend barriers of genre.

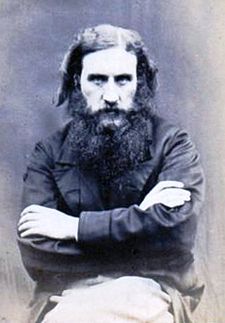

|

| Anne Thackeray Ritchie |

Examining Thackeray Ritchie’s

work emphasises the importance of supportive female communities: as an image

(sibyls), in practice, and as a point of intersection between biography,

creative writing and literary criticism (something beyond the scope of this

post is the influence Ritchie had on her niece, Virginia Woolf). I am, I

realize, more than verging on the borders of sentimentality here, but this

issue has a strong personal resonance for me at the moment. Over the past

year, I’ve been undergoing some really quite serious and frustrating health

problems, which (hopefully!) should be somewhat ameliorated soon, but at the

moment, leave me feeling rather isolated at times. One thing that has

been a significant encouragement for me throughout this experience is

co-organizing a research initiative, Reading

the Fantastic, which started last year with two other female

colleagues (Ikhlas and Sarah), and now includes two more co-organizers (Huwaida

and Rose). It’s very energizing to be working with people who share my

passion for fantasy – and interest in seeing how this genre serves as a point

of interconnection: for example, in our reading group sessions, we each suggest

texts from our various points of expertise, which means that my Victorian

fantasy perspective can meet East Asian, Malaysian, Kenyan and Syrian fantasy

traditions. I’m also extremely excited to be expanding this interest in

different outputs: in addition to the reading group series, we’re now running a

seminar series and a conference plus workshop. But I could never

have done all this by myself, and particularly not while my health is being so

unhelpfully uncertain. I’m really lucky, not just to have these colleagues, but

also that they are patient and supportive and understanding.in times when my

health just doesn’t want to play ball.