I've recently, along with a couple of other postgraduates who are interested in fantasy literature, begun a reading group which brings together fantastic texts from around the world, in which we each contribute a tale from our respective disciplines around a certain theme (more information here). For our session on 'Fantastic Journeys', I chose 'The Tale of Mr Fox', a tale which, though similar to the Bluebeard/'Maiden-Killer' type (321/312a) told by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, differs in that the heroine both investigates and resists the murderer (this tale is actually part of 'The Robber Bridegroom' type 955). The heroine works out her own escape by telling of her journey to visit her suitor in stages which are punctuated by the mysterious refrain of 'Be Bold, Be Bold' she sees on gates and doors throughout this investigative journey; this refrain cumulates in the phrase 'Be Bold, Be Bold, But Not Too Bold, Lest That Your Life's Blood Run Cold'. At each point of punctuations, her suitor counters her tale by saying 'It is not so, nor was is not so, and God forbid it should be so!'. But the heroine, Lady Mary, continues her tale despite these counters to her narrative. (Reading the name Lady Mary in this context has a certain amusing resonance for Downton Abbey fans: watch your suitors, Lady Mary Crawley, lest your life's blood run cold.) Gradually, her audience is caught up in her narrative spell and turns on her suitor at the point of climax, when she reveals the blood-stained hand she has found in his house.

The version we read was published by Joseph Jacobs in his English Fairy Tales collection,and so has a particular context of community behind it. Jacobs was fascinated by collections of indigenous folk and fairy tales (he published a collection of Indian Fairy Tales and of European Folk and Fairy Tales, for example). He was keen to discover indigenous English fairy tales (as opposed to tales from Perrault and the Grimms - of course, it's difficult to tell how particular fairy tales have developed across geographical and chronological miles, and fairy tale scholarship reveals that such tales do not respect national boundaries). The 'indigenous'quality of these tales, to Jacobs, had cross-class resonances which he discusses in the 'Introduction' to English Fairy Tales: he wanted to give 'a common fund of nursery literature to all classes of the English people', and he deplores the 'lamentable gap between the governing and recording classes and the dumb working classes of this country —dumb to others but eloquent among themselves'. Jacobs adds annotations to the tales in his collection, perhaps seeking to legitimize these 'indigenous tales' by evoking the annotated versions of the Arabian Nights, published by Edward Lane ( various formats between 1838-1859) and Richard Burton (1885), which assisted in the gradual academization of fairy tale collecting. Lane's and Burton's annotations have since been questioned, and there are some references which Jacobs would have done well to include, but didn't. Jacobs's annotations to 'The Tale of Mr Fox' identify it as being part of 'The Robber Bridegroom' type (linking it to 'The Oxford Student'), but strangely he doesn't mention another version of the 'Robber Bridegroom' tale which is a)written by an Englishman and b) features an English working class storyteller. This version is 'Captain Murderer'(1860) by Charles Dickens, and it contains fascinating parallels to 'The Tale of Mr Fox', particularly regarding the agency of female narrators.

'Captain Murderer' also features a serial killer and a bride who investigates and defeats the killer. References to Dickens's childhood nurse place 'Captain Murderer' in a social context, and a reference to 'Bluebeard' ('This wretch must have been an offshoot of the Blue Beard family') place it in both a literary (Perrault) and (apparently) oral tradition (Grimms). However, the agency of the investigative bride in this tale is somewhat compromised by the fact that she dies, though she dies willingly and uses her death to defeat the serial killer.

'[M]uch suspecting Captain Murderer, she stole out and climbed his garden wall, and looked in at his window through a chink in the shutter, and saw him having his teeth filed sharp [ . . .]Next day they went to church in the coach and twelve, and were married. And that day month, she rolled the pie-crust out, and Captain Murderer cut her head off, and chopped her in pieces, and peppered her, and salted her, and put her in the pie, and sent it to the baker's, and ate it all, and picked the bones. But before she began to roll out the paste she had taken a deadly poison of a most awful character, distilled from toads' eyes and spiders' knees; and Captain Murderer had hardly picked her last bone, when he began to swell, and to turn blue, and to be all over spots, and to scream. And he went on swelling and turning bluer and being more all over spots and screaming, until he reached from floor to ceiling and from wall to wall; and then, at one o'clock in the morning, he blew up with a loud explosion.'

Dickens's tale extends the audience into a cross-class community, as Caroline Sumpter has observed in discussing Dickens's 'attempts to capture the immediacy and the thrill of oral culture' which 'claim links to a storytelling tradition that will outlast the commercial moment' in her monograph The Victorian Press and the Fairy Tale (2008). (25) While his tale dramatizes the power of an oral working class storytelling over a middle-class child, Sumpter points out that his tale represents a written working class origin as well:

[A]s Dickens told John Foster, such haunting tales came from print as well as oral contexts: from his regular childhood purchase of the ‘penny blood’ the Terrific Register. In fact, the tale of cannibalism recalled in ‘Nurse’s Stories’ bears more than a passing resemblance to an urban myth that originated in a more recent penny magazine: the tale of the barber Sweeney Todd, which appeared in 1846 in Edward Lloyd’s The People’s Periodical.' (25-26)

Dickens's tale overtly recognizes working class orality, but not working class literature. However, comparing Dickens's 'Captain Murderer' to 'The Tale of Mr Fox' highlights the issue of who is able to tell tales, and how they tell these tales. It's interesting that the working class heroine in Dickens's tale is unable to share her experience with her community, but Lady Mary has the freedom to escape death by telling her community the tale of her adventures. By introducing his working class nurse and including dramatic descriptions of her narrative power over him, Dickens complicates this class dynamic. The description of the nurse telling the tale represents skills of narrative agency which Lady Mary demonstrates, though the nurse's skills are even more vivid:

'The young woman who brought me acquainted with Captain Murderer, had a fiendish enjoyment of my terrors, and used to begin, I remember as a sort of introductory overture by clawing the air with both hands, and uttering a long low hollow groan. So acutely did I suffer from this ceremony in combination with this infernal Captain, that I sometimes used to plead I thought I was hardly strong enough and old enough to hear the story again just yet But she never spared me one word of it.'

The powerful voice of the female nurse contrasts with the voiceless heroine; to this dynamic, Dickens observes his own voicelessness -- as a child. By narrating the tale in his own publication context as owner and editor of All the Year Round (the tale appeared in this periodical on September 8th, 1860), the fact that this tangle of silence and narrative captivation has, of course, increased his professional voice is clear, both to Victorian and subsequent readers. Consequently, Dickens's text depicts both the working-class nurse and the middle-class author as capturing audiences through re-telling the chilling story of the brave, intelligent, yet voiceless heroine of 'Captain Murderer'. Our reading group discussion raised the question of whether Lady Mary, in 'The Tale of Mr Fox', would have gained the support of her community had she not built it through dramatic narration (the upper class heroine in this version does not end well, for example): does her storytelling ability give her a social voice which she might not otherwise have? Reading Dickens's tale in the light of such questions highlights how 'Captain Murderer' dramatizes the ambiguities, not just of cross-class agency, but around the perceptions of such agency. Dickens's text extends this ambivalence into asking what creates these ambiguous perceptions and what propels the storyteller's voice, while providing dating advice at the same time: if you meet a guy whose last name is 'Murderer', please do a background check first, AT LEAST.

Exploring issues around Victorian fantasy and perceptions of the Victorians.

Showing posts with label Victorian. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Victorian. Show all posts

Tuesday, 11 March 2014

Friday, 12 April 2013

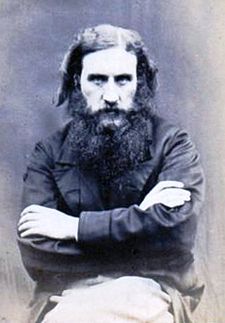

George MacDonald and Imaginative Engagement

The Victorian novelist George MacDonald, though well-known and well-regarded in the Victorian era (particularly by figures like John Ruskin and Lewis Carroll), is often forgotten today, as the editors of the recent Rethinking George MacDonald: Contexts and Contemporaries put it: ‘His ideas fell out of fashion, and the majority of MacDonald’s works were relegated to dusty library shelves’. (Glasgow: ASLS, 2013) Certainly, the combination of the fantastical and the spiritual in many of his works does not suit all tastes; similarly, not all readers will enjoy the moments in his realist novels which focus on moral development. (Though they are often enjoyable no matter what one’s taste for morality might be: Donal Grant, for example, contains drugging, hallucinations, a mad villainous Earl, and not just one but two skeletons in the attic.)

But no matter what one may think of George MacDonald’s answers, the questions he raises are always intriguing and direct his audience in search of nuanced insight, particularly on the way the imagination functions and the way in which we engage with it. In his own time, he was at the centre of many Victorian debates. His belief in the shared masculine and feminine nature of the Christian God chimed in with contemporary arguments made by the mid-Victorian feminist Langham Place Group as part of their fight for increased roles for women in public life. He encouraged his friend Octavia Hill in her efforts to transform tenement housing.

MacDonald also believed strongly in the social value of the poetic imagination, arguing for its role in investigating ‘the very nature of things’ in his 1867 essay ‘The Imagination: Its Effects and Culture’:

‘It is the far-seeing imagination which beholds what might be a form of things, and says to the intellect: "Try whether that may not be the form of these things;” which beholds or invents a harmonious relation of parts and operations, and sends the intellect to find out whether that be not the harmonious relation of them’. (‘Imagination’, p. 12)

‘The end of education [ . . .] is a noble unrest, an ever renewed awaking from the dead, a ceaseless questioning of the past for the interpretation of the future, an urging on of the motions of life, which had better far be accelerated into fever, than retarded into lethargy.’ (‘Imagination’, p. 1)

MacDonald locates this interrogative imagination in humility: ‘We dare to claim for the true, childlike, humble imagination, such an inward oneness with the laws of the universe that it possesses in itself an insight into the very nature of things.’ (‘Imagination’, pp. 12-13) In another essay, ‘The Fantastic Imagination’ he emphasises the importance of valuing anyone and everyone’s interpretation of a work of art, using the example of a fairy tale:

‘Everyone [ . . .] who feels the story, will read its meaning after his own nature and development: one man will read one meaning in it, another will read another [ . . .] [Y]our meaning may be superior to mine.’ (‘Fantastic Imagination’, pp. 316-317)

This valuing comes with the acceptance of his audience’s possible disagreement and disengagement with his work:

‘A genuine work of art must mean many things; the truer its art, the more things it will mean [ . . .] It is there not so much to convey a meaning as to wake a meaning. If it do not even wake an interest, throw it aside. A meaning may be there, but it is not for you.’ (‘Fantastic Imagination’, p. 317)

MacDonald sends his work out into the unknown with a shrug of his shoulders: ‘Let a fairytale of mine go for a firefly that now flashes, now is dark, but may flash again.’ (‘Fantastic Imagination’, p. 321)

I hope to use MacDonald’s ideas to shape my own approach to engagement and to avoid the paternalistic dissemination that Rivett criticizes. I have recently, in collaboration with other MacDonald scholars, launched an online engagement experiment in which we are re-imagining MacDonald’s fairy tale novella The Light Princess through a mixed-media blog: in two-weekly intervals, there is a post on each chapter containing a digital recording of the chapter, a new illustration created for the post, and a reflection by a different MacDonald researcher. I hope that this multi-faceted context will allow for discussion and the sharing of ideas. However, I accept it may well not do so, and not in ways that I might expect. We do not know who might appreciate it and to whom MacDonald’s tale, and our re-tellings, might appeal (if at all). Yet, I hope that, at the very least, it will become a place to share in the pleasures of the imagination (‘a firefly that now flashes, now is dark, but may flash again’), and so we launch our experiment into the unknown.

‘The Imagination: Its Functions and Culture’ in A Dish of Orts (London: Sampson Low, Maeston, Searle and Rivington, 1882), pp. 1-42.

‘The Fantastic Imagination in A Dish of Orts (London: Sampson Low, Maeston, Searle and Rivington, 1882), pp. 313-322.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)