George MacDonald and Imaginative Engagement

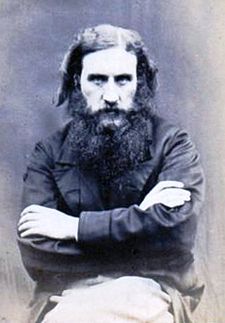

The Victorian novelist George MacDonald, though well-known and well-regarded in the Victorian era (particularly by figures like John Ruskin and Lewis Carroll), is often forgotten today, as the editors of the recent Rethinking George MacDonald: Contexts and Contemporaries put it: ‘His ideas fell out of fashion, and the majority of MacDonald’s works were relegated to dusty library shelves’. (Glasgow: ASLS, 2013) Certainly, the combination of the fantastical and the spiritual in many of his works does not suit all tastes; similarly, not all readers will enjoy the moments in his realist novels which focus on moral development. (Though they are often enjoyable no matter what one’s taste for morality might be: Donal Grant, for example, contains drugging, hallucinations, a mad villainous Earl, and not just one but two skeletons in the attic.)

But no matter what one may think of George MacDonald’s answers, the questions he raises are always intriguing and direct his audience in search of nuanced insight, particularly on the way the imagination functions and the way in which we engage with it. In his own time, he was at the centre of many Victorian debates. His belief in the shared masculine and feminine nature of the Christian God chimed in with contemporary arguments made by the mid-Victorian feminist Langham Place Group as part of their fight for increased roles for women in public life. He encouraged his friend Octavia Hill in her efforts to transform tenement housing.

MacDonald also believed strongly in the social value of the poetic imagination, arguing for its role in investigating ‘the very nature of things’ in his 1867 essay ‘The Imagination: Its Effects and Culture’:

‘It is the far-seeing imagination which beholds what might be a form of things, and says to the intellect: "Try whether that may not be the form of these things;” which beholds or invents a harmonious relation of parts and operations, and sends the intellect to find out whether that be not the harmonious relation of them’. (‘Imagination’, p. 12)

‘The end of education [ . . .] is a noble unrest, an ever renewed awaking from the dead, a ceaseless questioning of the past for the interpretation of the future, an urging on of the motions of life, which had better far be accelerated into fever, than retarded into lethargy.’ (‘Imagination’, p. 1)

MacDonald locates this interrogative imagination in humility: ‘We dare to claim for the true, childlike, humble imagination, such an inward oneness with the laws of the universe that it possesses in itself an insight into the very nature of things.’ (‘Imagination’, pp. 12-13) In another essay, ‘The Fantastic Imagination’ he emphasises the importance of valuing anyone and everyone’s interpretation of a work of art, using the example of a fairy tale:

‘Everyone [ . . .] who feels the story, will read its meaning after his own nature and development: one man will read one meaning in it, another will read another [ . . .] [Y]our meaning may be superior to mine.’ (‘Fantastic Imagination’, pp. 316-317)

This valuing comes with the acceptance of his audience’s possible disagreement and disengagement with his work:

‘A genuine work of art must mean many things; the truer its art, the more things it will mean [ . . .] It is there not so much to convey a meaning as to wake a meaning. If it do not even wake an interest, throw it aside. A meaning may be there, but it is not for you.’ (‘Fantastic Imagination’, p. 317)

MacDonald sends his work out into the unknown with a shrug of his shoulders: ‘Let a fairytale of mine go for a firefly that now flashes, now is dark, but may flash again.’ (‘Fantastic Imagination’, p. 321)

I hope to use MacDonald’s ideas to shape my own approach to engagement and to avoid the paternalistic dissemination that Rivett criticizes. I have recently, in collaboration with other MacDonald scholars, launched an online engagement experiment in which we are re-imagining MacDonald’s fairy tale novella The Light Princess through a mixed-media blog: in two-weekly intervals, there is a post on each chapter containing a digital recording of the chapter, a new illustration created for the post, and a reflection by a different MacDonald researcher. I hope that this multi-faceted context will allow for discussion and the sharing of ideas. However, I accept it may well not do so, and not in ways that I might expect. We do not know who might appreciate it and to whom MacDonald’s tale, and our re-tellings, might appeal (if at all). Yet, I hope that, at the very least, it will become a place to share in the pleasures of the imagination (‘a firefly that now flashes, now is dark, but may flash again’), and so we launch our experiment into the unknown.

‘The Imagination: Its Functions and Culture’ in A Dish of Orts (London: Sampson Low, Maeston, Searle and Rivington, 1882), pp. 1-42.

‘The Fantastic Imagination in A Dish of Orts (London: Sampson Low, Maeston, Searle and Rivington, 1882), pp. 313-322.